Turn back the clock to late October, 1938. Actor Orson Wells was lining up sci-fi radio plays for his Mercury Theater on the Air. He went through a few ideas, but none of them seemed to be working. Finally, somebody asked "How about this?" and pulled out the book War of the Worlds.

Wells was reluctant to adapt the work to the radio. Not because he was afraid of causing mass hysteria, but because he found the story "dull." The book had been around for 40 years, it had been adapted to several adventure stories and comic books by this time. Most people were familiar with this story, he thought. Finally he agreed to do it. But they had to update it before they went on the air.

Now, fast forward to 8 pm on Sunday, October 30th. A small number of radio listeners tuned into the Mercury Theater on the Air and heard the play's introduction, announcing that night's play as H.G. Wells' War of the Worlds. However, most people were tuned into the immensely popular Chase and Sanborn Hour, and missed the crucial intro. The first four minutes or so went well, but then at approximately 8:05, a rather unpopular singer came on the show. So people began to dial surf, and as it happened most people landed on the Mercury Theater on the Air first, already in progress. But when they landed on it, it sounded like a regular music show. Then, after a little musical interlude, a voice cut in: "We interrupt this program to bring you this news bullitin..."

Now, it should be mentioned at this point that news breaks were fairly new, and extremely frequent, in the late 1930's. Most news breaks at the time ran bullitins having to do with the Nazis, who had been slowly overtaking Europe. Naturally, Americans had been growing nervous about the Nazis, and there were only a few ways to get the news, radio often being the fastest.

The War of the Worlds news break reported that the Princeton Observatory had observed gas explosions on the surface of Mars at regular intervals, but the station would keep the audience updated should anything else be found. "And now back to the music of Raymond Roquello and His Orchestra."

Most people found this break to be a bit odd. Explosions on Mars? How strange. And who was this Raymond Roquello guy? Not really thinking much of it, folks sat back and relaxed again. But then about a minute later, another news break comes through: The Princeton Observatory had just reported the landing of a meteor in rural Grover's Mills, New Jersey, and had schedualed an interview with one of the Observatory's astronomers.

Now people were starting to get suspicious. What in the world was going on? Most people claimed they didn't believe the story too much, until they heard several "expert" opinions of the situation. The way the show was formatted, with the breaks over the music program, the authoritative commentary, made it sound completely legitament. Folks were lost inside the newscast.

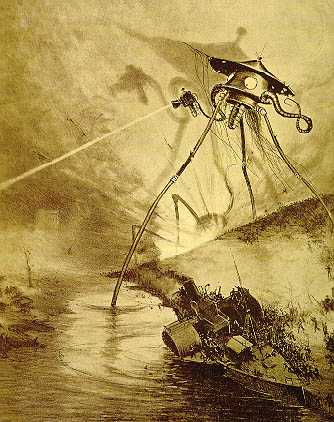

Finally the update cut to a field report in Grover's Mills, where the meteor had landed. The reporter and an astronomer are describing the events unfolding before their eyes: the meteor had fallen away, revealing a metal pod definitely of alien origin. After a few tense moments, the pod begins to open, revealing a hideous slimy creature; muffled shouts could be heard in the background. Then, out of nowhere, the reporter begins to flip out: the creature has just vaporized knot of military personell.

The reporter's panic sounded completely real, and oddly familiar. A year before, many people had heard the now-immortal cry of "Oh, the humanity!" in response to the Hindenburg disaster. The actor playing the reporter had actually found a tape of this report and listened to it repeatedly, so he could get into the right frame of mind for the attack scene.

Seconds later, without warning, the field report cuts out. Soon after, it is reported that the pod has sprouted tree-high legs and was marching through the New Jersey countryside, crushing anything in its path. This is where people really started to panic, although they didn't think "We're being attacked by Martians." Their first thought was, "We're being attacked by Germans."

The show continued on in the same way, as a string of news reports come in announcing that more Martians were landing and slowly taking over New Jersey and surrounding areas, taking out armies with a poisonous gas. At one point later in the broadcast the news announcer dejectedly states that "everything [was] wiped out."

About 12 million say they got the joke. But the majority of the American public didn't. No one knows exactly how many people panicked that night. However, there are a few certain numbers: The Trenton police department receieved 200 calls in under two hours. The New York Times switchboards were inundated with 875 calls alone, which were mostly people wanting to know where they would be safest. A study conducted shortly after the broadcast found that some people reported they actually felt like they were choking, a handful claimed they saw a veil of smoke over Manhattan from the battle in nearby Jersey, and some swore they spotted a marching Martian pod or two.

After the broadcast, and learning of the mass hysteria, Orson Wells held a press conference, in which he said this:

"The War of the Worlds has no further significance than as the holiday offering

it was intended to be. We annaihilated the world before your very ears, and

utterly destroyed the CBS. You will be relieved, I hope, to learn that we didn't

mean it, and both institutions are open for business."

In short: It was all a joke. Wells expressed great surprise that such a familiar story could cause such panic when the format was changed up a bit. Unfortunately the public and the FCC didn't find the situation funny, the FCC so much so that the comissioner shortly thereafter labled Wells and his Mercury Theater on the Air as "radio terrorists."

As if that wasn't enough, events similar to this have happened twice since 1938: once in Quito, Ecuador, in 1949, and in our own Buffalo, NY, in 1968. The format was that of a regular DJ show on WKBW, with a interruption format very similar to the original 1938 broadcast. The outcome was very similar as well: the station received 2,000 calls, 47 newspapers nationally reported the incident, even a portion of the Canadian army was dispatched to the border bridges to fend off the Martian invadors.

People, by nature, are hard-wired to latch onto stories and to follow them through to the end. Unfortunately some miss the crucial beginnings and misinterpret the whole thing.

Finally the update cut to a field report in Grover's Mills, where the meteor had landed. The reporter and an astronomer are describing the events unfolding before their eyes: the meteor had fallen away, revealing a metal pod definitely of alien origin. After a few tense moments, the pod begins to open, revealing a hideous slimy creature; muffled shouts could be heard in the background. Then, out of nowhere, the reporter begins to flip out: the creature has just vaporized knot of military personell.

Finally the update cut to a field report in Grover's Mills, where the meteor had landed. The reporter and an astronomer are describing the events unfolding before their eyes: the meteor had fallen away, revealing a metal pod definitely of alien origin. After a few tense moments, the pod begins to open, revealing a hideous slimy creature; muffled shouts could be heard in the background. Then, out of nowhere, the reporter begins to flip out: the creature has just vaporized knot of military personell.

This sounds almost identical to a radio progroam I heard by radiolab. Is the text from there? I adore Welle's broadcast, I think it was absoloutely brilliant, and I'm thrilled to see people writing about it :)

ReplyDeletehttp://www.wnyc.org/shows/radiolab/episodes/2008/03/07